Protecting the Baltic Sea: Uncovering gaps in MPA management

The Baltic Sea, one of the world’s largest bodies of brackish water, is home to a wealth of varied biodiversity. But this unique and delicate ecosystem is facing increasing pressures from human activities and global threats, such as climate change. A key strategy for safeguarding the sea is the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)—designated zones where human activities should be regulated for the benefit of biodiversity, allowing ecosystems to recover and thrive.

Despite globally recognized efforts by the countries bordering the Baltic Sea to designate MPAs, significant gaps remain in their governance, management, and monitoring—both individually and as part of a transboundary network. To address these gaps, the PROTECT BALTIC project—under the umbrella of the regional sea convention HELCOM—is working to better understand the current state of the Baltic Sea MPA network and its management across the region, as well as how countries can collaborate to enhance it. A key step in this process is updating and improving the region’s MPA Portal, a regional platform designed to store comprehensive MPA information and strengthen the capacity of marine protection actors.

In this process, the project is uncovering some notable challenges, but also some significant opportunities.

Estefania Cortez, PROTECT BALTIC Project Manager / Legal expert from CCB, is leading the task of collecting and compiling information from the Baltic countries’ MPA management plans and other similar official instruments. She provides insights into the complexities of MPA management in the region and the crucial role that the project is playing in modernizing information and bridging existing gaps.

A shared commitment to protecting the Baltic Sea

PROTECT BALTIC is a collaborative effort aimed at strengthening the designation, management, governance and effectiveness of MPAs across the Baltic Sea, with the goal of ensuring quality protection for marine life. Estefania explains, “Initially, our aim was to consolidate and analyze data on nationally recognized MPAs in the Baltic region. But as the project progressed, we realized that the landscape for management of these areas was far more complex than anticipated. Our role evolved from mere data collection to actively verifying and cross-checking information to ensure consistency and accuracy.”

The project aims to address the core challenge of fragmented and inconsistent management-related data across different countries, while also reducing barriers to accessing this information. Each nation has its own way of defining, managing, and documenting these areas and there is currently no regional platform where such information can be shared. As Estefania highlights, “While countries bordering the Baltic Sea have made significant strides in establishing MPAs, there remains a lack of a common, unified framework. Each country has its own regulations and management frameworks in place. Some areas, for example, are privately protected, while others are part of large national programs and key strategies. These variations make it difficult to assess and objectively compare how MPAs are being managed across the region as a whole."

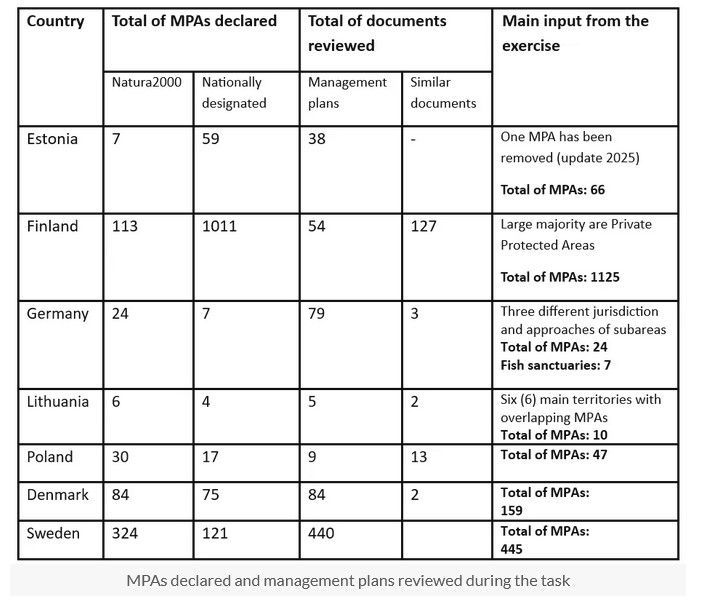

The work done so far in PROTECT BALTIC has already led to some groundbreaking results: through our data collection efforts, the number of MPAs documented in the region has increased tenfold. Initially, only 189 MPAs were included in the database, but with new submissions, this number has surged to an astounding 1,876 MPAs. Estefania explains, “A large part of the increase in data is a direct consequence of recent national efforts to continue designating MPAs while strengthening effective measures in those areas.”

Collating MPA management data to build a comprehensive picture

The core of this work involves compiling and updating information from MPA management plans—comprehensive documents that outline protection objectives, strategies, and actions for managing each MPA. These typically include details on protection goals, the pressures faced by the area, the specific measures in place to address these challenges, monitoring protocols, and enforcement actions. They are essential for understanding how each MPA is designed to protect marine ecosystems and ensure sustainable use.

Estefania explains, “Initially, the estimate for the number of available management plans ranged somewhere between 100 and 200. But it turned out there were far more than we anticipated—over 850 plans or similar documents across the region. This required us to rethink our approach and bring in additional support to extract key data from these documents.”

The task was complex, involving tracking down the documentation, analyzing the plans, and collecting and collating data. Since most plans are also only available in the national language of the country where the MPA is located, all the collected information also needed to be translated into English as part of the process. With each nation defining and managing MPAs differently, some lacked clear legal frameworks or official documentation, making data interpretation challenging. To address this, the team developed a structured methodology for extracting the data, which was continually tested and refined as specific documents required additional guidance.

A group of nine trainees, with expertise in environmental and data management and fluency in at least one of the Baltic Sea languages, was onboarded. Each trainee focused on a specific Baltic country, except for Sweden, where three trainees were needed to handle the high volume of management plans. Estefania notes, “We quickly realized that translating every single document in its entirety would be too costly and time-consuming, so we trained the team to extract relevant information in their local languages and condense it into a standardized Excel format. We further utilized pre-determined internationally agreed lists on species and habitats, as well as information on human activities and pressures produced within the project.”

Harmonizing the data was yet another challenge, as countries defined threats, management measures, and conservation goals in unique ways, sometimes also between areas or area types within the same country. Despite the varied levels of detail in the plans, the team remained flexible and methodical in extracting relevant information.

What has been collected?

The key categories of information collected include:

- Basic MPA details: name, code, designation year, type, management plan status, IUCN category, stakeholder engagement, and transboundary elements.

- Protected features: species, habitats, ecological functions as well as cultural heritage and ecosystem services, whenever possible.

- Human activities and pressures: including shipping, fishing, tourism, and pollution, utilizing the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) and Water Framework Directive (WFD) as references.

- Protection measures: ranging across the whole span of human activities and from seasonal restrictions to full no-take zones.

- Monitoring efforts: identifying the direct inclusion of ecological or human activities monitoring in the area. The data has been gathered from official national MPA lists, government institutions, legal sources, and ongoing conservation projects such as Biodiversea in Finland.

Challenges, lessons learned and country profiles

Although the large volume of collected data still requires further processing, and national consultation and review before detailed conclusions can be drawn, one of the key takeaways from this work has been the significant diversity in how MPAs are designated and managed across the Baltic region. Some countries, like Germany and Finland, have multiple jurisdictions responsible for MPA oversight, leading to variations in management plans within the same country.

A major issue uncovered is the lack of marine-specific protection measures in many MPAs. This raises concerns about the effectiveness of existing protections and highlights the need for adaptive management strategies that allow for the modification or expansion of protection measures as knowledge improves and the dynamics affecting the ecosystem change.

Another significant challenge has been gaps in data comprehensiveness and the availability and accessibility of data. Many management plans either lack critical information or exist only in non-digital formats, complicating data gathering and analysis. Additionally, some countries experienced delays in providing up-to-date documents, either because the information wasn’t available digitally or because the plans were still under revision.

“The data gaps became very clear after we received the first round of information from the countries,” Estefania Cortez explains. “Some management plans were missing or incomplete, and in some cases, MPAs themselves were not listed correctly. This is a problem because, without accurate data, we can’t measure the effectiveness of protection efforts or understand where and what additional measures are needed.”

While the team has gathered substantial amounts of data—far more than initially expected—Estefania notes, “We have gathered enough data to highlight key trends and challenges, but protection planning requires a comprehensive understanding that goes beyond just data points. This includes broader ecological, economic, and social contexts, which are being actively addressed under other work packages within PROTECT BALTIC.”

To make the management data as useful as possible, it’s crucial to consider both what has been collected and how it is applied. In some cases, there are challenges with data-sharing between countries or institutions, which can result in incomplete or outdated information being available. Moving forward, refining the datasets to ensure they are comprehensive and applicable will be essential.

The data collection showcased the different approaches each country has adopted:

- Denmark: The team reviewed 85 management plans covering different types of MPAs, including Natura 2000 sites and other protected areas. However, 51 MPAs have been recently added and are currently being reviewed.

- Estonia: 38 management plans were reviewed, but many MPAs have overlapping areas with multiple protected area categories, adding an important factor into the assessment process.

- Finland: The most complex case, with over 1,000 MPAs (including Private Protected Areas). Often these sites fall under multi-management plans, meaning that a single document can cover multiple MPAs.

- Germany: 82 management plans were reviewed. The country’s approach to MPA management is highly jurisdictional, with different rules applying to MPAs depending on the federal and state governance levels.

- Lithuania: Only 7 management plans or similar documents were assessed, as most MPAs fall under larger territorial conservation programmes rather than standalone sites.

- Poland: The team analyzed 22 management plans, which highlight the varied pressures affecting MPAs, from industrial development to tourism.

- Sweden: With 148 management plans reviewed so far, and 292 still being checked, the trainees are exploring the use of AI to assist and speed up the data extraction process, especially for identifying protected species and habitats within a specific MPA.

An important decision was made regarding Latvia and Åland. Both Latvia and Åland are separately undergoing full-scale revisions of their suite of management plans, with updates expected to be finalized only in the second half of 2025.

“If we included their current management plans in our dataset at this stage, they’d be outdated before they could even be added to the database,” Estefania explains. “So, we decided to wait until their new plans are finalized to ensure we use the most accurate and relevant information. In the meantime, we stay in constant communication with the relevant authorities to track the progress of their updates.”

Filling in the blanks

A central aspect of the work has been gathering data on the pressures faced by MPAs, such as overfishing, pollution, and climate change, as well as the mitigation measures being implemented, like fishing restrictions and habitat restoration. While some of this data has been useful, Estefania points out that certain gaps remain: “We are still completing the overarching MPA landscape. There is a lack of data regarding the intensity and location of the pressures. We need more detailed information on how these pressures are affecting specific areas and how effective the mitigation measures have been.”

To address this, PROTECT BALTIC is currently working on advancing the spatial modelling of human activities and the resulting pressures, including identifying what pressures are suited for management at MPA level.

Another significant gap is the limited data collected on MPA monitoring, which is essential for assessing whether management measures are being followed. Estefania explains, “Some countries focus on compliance, while others prioritize ecological tracking. We need to ensure that monitoring systems are standardized, cover both ecology and human activities, and are regularly updated. Opportunely, this in-depth research will be further explored by the Monitoring work package within the project.”

The way forward: a unified approach

Looking ahead, PROTECT BALTIC is preparing to analyze the second round of data collection, which was open until February 2025. This round has focused on addressing gaps and refining the initial findings, filling in missing details, cross-checking discrepancies, and ensuring that the dataset is as robust as possible. While the first data call primarily identified MPAs, this phase focuses on understanding how they are managed and protected through specific sectorial measures. The last step in the process will be populating the Baltic Sea MPA database and inviting the countries to review and quality check the data before it is made publicly available.

Estefania emphasizes, “The success of the project depends on collaboration with all Baltic Sea countries. We need their active involvement to validate the data we’ve collected, and we also need their feedback throughout the project to improve the MPA Portal. The more data we can collect, the better we will understand the challenges facing the Baltic Sea, and the better we can recommend suitable solutions to protect these areas.”

This second phase will also gather additional information about national legal frameworks, sectoral instruments, and other factors influencing MPA management. The insights gained will be instrumental in shaping future conservation strategies and recommendations, ensuring that the work translates into tangible policy and conservation actions that protect biodiversity.

***

Article written by Paul Trouth, Communication Coordinator (PROTECT BALTIC), and available also on the

PROTECT BALTIC´s webpage.

This crucial work on mapping and analyzing MPA management plans will be presented at the 4th EU Blue Parks Community Workshop in Brussels on 6 March 2025, during European Ocean Week.

Estefania Cortez, alongside Jannica Haldin, PROTECT BALTIC's Project Manager, will share insights on the challenges and progress of the project in ensuring sufficient protection and restoration of the Baltic Sea’s marine environment. Their presentation will be part of the session on the state-of-play of strict protection in European seas.